WOLE SOYINKA

Unsinkable City

Wole Soyinka reflects on a lifetime in Lagos*

Going to the

Portobello Road Market for wosi-wosi— the Yoruba name for odds and ends,

antiquities true and fake, and general bric-a-brac of even unmapped nations—has

remained my routine destination whenever I find myself in London. It may have

commenced in curiosity, provoked by the aqueous association of names—Portobello,

Beautiful Port; Lagos, Lakes, originally Lago de Curamo—I can only

testify that it all began while I was a student in mid-1950s and has remained

ever thus. Periodic forays into Britain even decades after my first student

incursion have failed to diminish the tug, despite deleterious changes at the

Lagos end of the axis. Each visit still registers personal correlations, some

stimulating, others sobering. It is no longer the innocent, prying eye on

antique oddities, ogling, desiring and caressing art objects of dubious

pedigrees; it is now both attraction and repulsion, but always evocative—in absentia—of

that amphibious city, thousands of miles away, called Lagos. It was the

official capital, once upon a time, but it is still the commercial capital of

the most populous, and perhaps most unmanageable, black nation of the world:

Nigeria. Lagos exerts a secretive, sometimes resented, but tenacious hold on

all who pass through its steamy streets and tumultuous markets. Do not take my

word for it. Ask any foreign resident or mere bird of passage through that

frustrating capital. The accustomed expression is, “You can take the expatriate

out of Lagos, but you cannot take Lagos out of the expatriate.” The less

charitable version goes, “Lagos is akin to a mosquito bite: the malaria spores

never completely leave your bloodstream.” The ever-popular high-life song with

fluctuating lyrics that give away recent peregrinations of whichever band

leader appear to settle the matter once and for all, applicable even to

Portobello addicts, but with increased dosage of disenchantment:

Lagos is the place

for me

Lagos, this lovely

city

You can take me to

England and Amerikay

Keep your Paris or

Roman city

Give me Lagos any

day

Lagos, for my

temperament, is perhaps best enjoyed vicariously and in small doses. Luckily,

the city shares many features with the antique mart or, perhaps less

glamorously, a flea market. Sometimes one feels that the world’s discards, the

detritus of the constantly surging ocean, eventually come to rest on the

beaches of Lagos. No wonder, the argument also rages forth again and again,

especially at election time, that Lagos is a no-man’s land. Historical facts

jostle with myth, migration waves with politics of concessions, attributions

and conquest. Were the monarchs of Lagos truly vassals of the Benin kingdom, or

was Benin a mere occupation force on military camps established in parts of

Lagos island? Does the name by which a large Lagosian group of settlers, the

Awori, are known, truly derive from the triumphant cry Awo ri? This

would lend credence to the Lagosian origin myth that claims a roving hunter

from the Yoruba hinterland, having decided (or been forced) to migrate with his

people, consulted Ifa, the Yoruba divination system. The outcome was

instruction that he place a bowl on a stream and follow its progress. Wherever

the bowl sank—ibi ti awo ri— that was the destined habitation.

Lagos’s numerous ties

to the ancient Benin kingdom—culture, trade, indigenous names, etc.—are not

disputed, only the details. A Yoruba war leader wrote a unique chapter in war

chivalry by journeying for several weeks just to return the corpse of his slain

foe, a Benin war commander, to the king, the Oba of Benin. As a reward, the

king sent him back as regent over one of the Benin war camps and its zone of

authority. Just as strong are the claims of another set of “true owners”—the

Idejo, the Olofin, plus the radiating lines from a great hunter, Ogunfunmire.

Ogunfunmire wandered in from the heart of Yoruba land and founded Isheri, from

where his 12 descendants fanned out along the coast and farther inland to

establish a clan dynasty. Was that the same hunter? Or a different ancestor

entirely?

The Lagos of today is

what preoccupies, agitates, repels and seduces, and from widely different

causes. Lagos is truly a Joseph-city, a garment of many colors, textures and

stylists. Try to imagine a straight line, drawn from any point on the border of

Lagos across its land mass until it terminates at the beach. Walk that straight

line through buildings, markets, lagoons, canals, upscale and hole-in-the wall

shops and residences, flyovers and clotted streets, shrines, parks, warrens,

mosques, churches, etc. You would end up surfeited by sheer variety, like a

jumbo meatloaf attempting to set the world record in the stuffing of

incongruities. I suspect that it was a whiff of that wanton ecumenism of

identities that I sensed in those stalls of Portobello markets at my very first

visit as an impressionable youth. I gratefully found it a generous,

accommodating substitute that served as relief from the notorious British

inhospitable and insular character, plus the unpalatable weather menu of the

1950s—cold, wet and dismal.

But even as Portobello

began to burst its bounds, both in its capture of neighboring streets and

enlarged cosmopolitanism in its offerings, opening out to other continents, so

did Lagos begin to expand, become more haphazardly textured, more daring, with

insertions of thematic galleries and mobile stalls, its squares and traffic

islands pocked also by itinerant performers and lethargic to enraptured

audiences, vanishing into endless by-streets and cul-de-sacs, in and out of

festive seasons. The pace has become so rapid that it is hard not to imagine a

Lagos of the future, prefigured in those intensive transformations, including

new hordes of visiting or relocated nationalities—Japanese, Chinese, Caribbean,

and other babblers in their own tongues and accented English. Let us traverse

backward through the years to a significant fin de siècle transitional phase in

the life of this writer, for a sampling of human and other exotic wares.

Occupational risks, of

the political extracurricular kind, eventually prescribed exile. I returned to

Nigeria in 1999 after a compulsory spell outside her borders, an exile of some

four years. Before that hasty departure, I had lived mostly in my hometown, the

rockery encrusted city of Abeokuta, but also with a foot in Yaba, a Lagos

suburb where the trees had not been eaten, and even enjoyed residential,

integrated status. By then, I had long terminated a career of regular teaching

at my former university in Ile-Ife. It had served as the transient third of a

residential triad of unequal occupancies. The other two were Abeokuta, maternal

home, and Isara, paternal, a small town of unremitting red laterite whose dust

permeated even the human skin, giving it a russet pigmentation.

Back from exile, I

found myself obliged to seek another toehold in Lagos. I found one, right on

the island itself and close to a sandy stretch known as Bar Beach, largely a

weekend and holiday relaxation recourse that also serves as a buffer between

the Atlantic Ocean and the newly developed residential zone known as Victoria

Island. That habitation sometimes felt, in some ways, a further extension of my

exile, as so much of it had changed. My awareness of the sea, from childhood

vacations spent in Lagos, had been formed by friendly surf and wave-sculpted

sand. Nature was then at its most placid and collaborative, in peaceable

partnership with the lagoon and sluggish canals that threaded the marshy

islands—Obalende, Ebute Metta, Ikoyi. Apapa, Isale Eko—each wet surface with

its own network of plying canoes, shacks and shanties, cries and gurgles,

whispers and raucous sales chants and dark silences, even in brutal daylight.

Abeokuta of the rocks

was my principal home, Isara a stolid, impregnable linkage with time past.

Lagos of the canals was my escape into exotica, yet also within the seamless

consciousness of a personal proprietorship that comes with affinities. Bar

Beach was still a stranger to public executions of armed robbers, by firing

squad, under a military regime, a spectacle that was open to all non-paying

audiences, including children. Until then, that beach was little more than a

home to makeshift churches—more accurately, bamboo and palm fronds around a

cross-topped mound of sand, the cross itself sometimes made from fresh palm

fronds. They were presided over by colorful charlatans who would later people

such plays as The Trials of Brother Jero and even pop up in everything from

cameos to major roles in stories such as my novels The Interpreters and Season

of Anomie. My mother being an itinerant trader, and with a family line

stretching through Lagos, the lagoon city became a mere extension of the

maternal home, Abeokuta.

So did the markets. I

grew up familiar with all the open-air markets—Ita Faji, Iddo, Ebute Metta

Sangross—a name derived from a corruption, it is claimed, of the sand grouse

that once populated the area. I did eventually take to the hunt, but as I was

not remotely close to conception at naming time, and no historian has traced my

ancestry to the alleged founder of Lagos (the hunter Ogunfunmire) I could not

be held responsible for the extinction of the grouse population. I do not even

know what a sand grouse tastes like. It was a different matter from the

flavors, smells, colors and sounds of the market itself, identical—except for

the riveting forms, the heady smells of freshly delivered fish, crabs and

lesser shellfish—with the markets of Ibarapa or Iberekodo in Abeokuta. All

provided a medley of sensations that relegated Portobello to the ranks of

deodorized human spaces, nonetheless irresistible. But then, I was prejudiced.

My vacation home in Lagos was Igbosere Street, just a stone’s throw from Sangross.

To seal an unspoken pact, one of the more famous juju bands took up residence

in a night-shack that opened its doors after the market women had departed. It

became a favorite haunt after I joined the ranks of lawfully and lowly employed

school leavers.

My mother, that

enterprising lady, had her main shop in Ake, Abeokuta, quite close to the

palace, reigned over by a monarch who exuded much mystery and dignity until his

downfall at the hands of rebellious women in the famous anti-tax riots of the

1940s. They were led by my aunt, the feisty Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti—name sound

familiar? Substitute Ransome with Anikulapo, and the equation reads Anikulapo

Kuti—yes, the Afro-beat king, Fela Anikulapo Kuti, who dominated the Lagos—then

the entire Nigerian— music scene, extending into the continent, the Diaspora

and even Europe. France was certainly the earliest European conquered

territory. Fela’s “Afrika Shrine” remains a pilgrimage destination today for a

cross-section of avid music consumers or simply the merely curious—indigenes

and expatriates, diplomats and the underworld, even foreign presidents with a

yen for the raw, raunchy and raucous. His sons, also musicians with their own

bands, keep up the legacy, including a guaranteed line for the fattest smoke wraps

to be encountered in the world’s republics of nightlife.

That much, at least,

has not changed. An extension of that shop, in a coincidence that took years to

register in my mind, was my mother’s stall in Isale Eko, near Iga Idunganran,

the seat of another monarch, the Oba of Lagos. We shared our vacations between

Lagos and my paternal home, Isara, a city bereft of either rocks or canals; it

had just a stream, and a deep wooded spring that appeared to be the source.

Isara was a somewhat in drawn village of supernatural and numinous forces,

steeped in tradition.

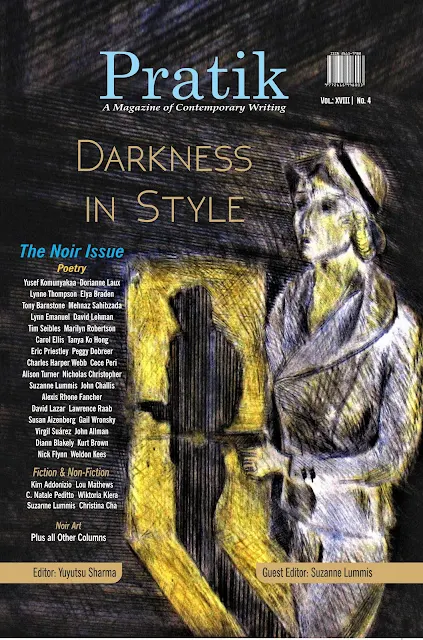

For Full version, pls

read the print edition of Pratik’s current Issue

(*First published by Stranger’s

Guide in 2020)

Wole Soyinka is a Nigerian playwright, poet, author,

teacher and political activist. In 1986, he received the Nobel Prize for

Literature. A towering figure in world literature and a multifaceted

artist-dramatist, poet, essayist, musician, philosopher, academic, teacher,

human rights activist, global artist, and scholar, he has won international

acclaim for his verse, as well as for novels such as Chronicles from

the Land of the Happiest People on Earth. His works encompass drama,

poetry, novels, music, film, and memoirs; he is considered among the great

contemporary writers He is the author of several collections of poetry,

including Mandela’s Earth and Other Poems, two novels, books

of essays, and memoirs, including The Burden of Memory, The Muse

of Forgiveness, and numerous plays. Soyinka has held positions at Harvard, Yale, Duke, Emory,

and Loyola Marymount in the US, as well as highly regarded institutions

throughout Africa and Europe.

Also Available

on Amazon & Flipkart

Amazon USA: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0D9B5Q85J?ref=myi_title_dp

Amazon Canada: https://www.amazon.ca/dp/B0D9B5Q85J?ref=myi_title_dp

Amazon India: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0D9B5Q85J?ref=myi_title_dp