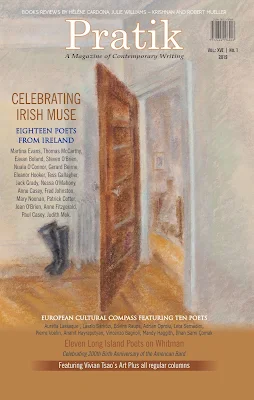

Doorway at

Dusk: From Jeddah to New York

One winter afternoon when I passed through the door to the

room in the back, I saw that the sun had cast shadows of the brown door on the

off white wall. A pair of tall boots stood next to the radiator. Outside the

door was a bluish hallway. There were a small framed photo and clothing that

was left on the rail. I suddenly saw a painting. I brought my easel to the

narrow room and began the pastel.

In the moment to moment dialogue with light, I tried to

capture what was in front of me. I discovered that the tones of the white

doorframe kept on changing as the tones of the hallway continued to deepen. I

did not work with any formula. Painting was like sailing out to the unknown.

I often worked in silence. In February, the symphonic play

of color and light in pastel gradually took shape. One afternoon at the end of

the session in 2017, I brought the easel back to the studio. In the bright

light in New York, I studied the picture and realized that I had just added the

last stroke to the new painting Doorway at Dusk. I put down the worn stick in

my hand.

It was in late summer 1977 that I landed in Jeddah, Saudi

Arabia. I joined my husband who was teaching there. I had received an M.F.A.

degree in painting from Carnegie Mellon University in the U.S. As if a dream had

come true, I visited for the first time Paris and Rome on my way to the Middle

East.

In the ride from the airport to our new home, I noticed

outside the car window a giant setting sun. Its flaming red figure seemed to

rest forever on the horizon. Yet suddenly, it left without a trace over the

desert.

My sunny studio was on the second floor of an apartment

building on the street corner. In early afternoon, a shepherd dressed in a robe

often passed by with his goats. The melodic sound of the brass bells around

their necks broke the silence of the sandy street.

As the package of my brushes and oil paints had yet to

arrive, I thought of visiting the local graphic supply store. To my surprise, I

came across a set of 200 pastels. Its fine gradations in red, yellow, blue and

green impressed me. When I began exploring it the next day, I felt a strange

familiarity with the new tool. I sensed that it opened a channel in blending

and in creating the nuanced tones in my picture.

When I set up the easel in front of the mirror in my new

studio, I noticed that the steady sun had outlined the features of the young

woman in the reflection. The light in her eyes and the flowers on her veil

intrigued me. I began painting without hesitation. In the process, I felt a

sense of liberation. I was no longer concerned about the self. Ignited by

curiosity, I used pastel and my finger to create on paper the tones and

textures of my subject.

Several months after I arrived In Jeddah, I realized that I

no longer tried to resolve my painting through theoretical thinking. In pastels

such as Self-Portrait with Veil and The Poet, I jotted down my spontaneous

responses to light.

When I saw for the first time the artworks by Spanish master

Antonio Lopez Garcia in New York in 1986, I was struck by the intimate touch of

his hand. The retrospective show included oils, drawings and sculptures by the

Magic Realist. I felt an affinity with the works from life of his daughter

Maria and of his uncle, painter Antonio Lopez Torres.

His nuanced drawings in pencil sometimes took years to

complete. In infinite changing tones, he captured child Maria in a peacoat. Her

presence was gentle, modest and contemporary. In the drawing Antonio Lopez Torres’House, the elderly

artist passed through the familiar interior in layered silvery light. The back

of Torres in an overcoat drew me in as if in a dream. Whether a window scene of

a street or a mural-sized cityscape, Lopez created images over long periods of

observation. The emotions triggered by his brush were subliminal. They suppress

yet transcend.

Recently, in the narrow room in New York, the afternoon sun

from the two tall windows shined on the Chinese scroll on the wall. The

rhythmic strokes of Chinese calligraphy by my father took me back to his study

in Taipei shortly before I left for graduate studies in the U.S. He wrote the

poem by Li Yi-shan in Tang Dynasty at my request. He carefully stamped his seal

in red ink after writing. Nearby, the bronze-toned spines of the books World

Art Series published by Kawade Shobo in Japan stood on the hand-made bookcase.

Before I had a chance to see the original artworks by Corot and Cézanne, the

series was my Western art museum.

My middle school was within walking distance from the

National Palace Museum in Taiwan. I longed to visit the Museum in construction

outside my classroom window. My first visit in 1965 led me to the discovery of

the hand scroll by Emperor Hui-tsung of Sung Dynasty. In his personal slender

gold style, he wrote the Poem. I felt transported when I read the last lines of

his writing. On darkened silk, the bouncing strokes of the palm-sized

characters read,

“ The dancing butterflies lost their way on the fragrant

path

Their wings chased

after the evening breeze.”

The scrolls of Hui-tsung and of the landscapes by Chinese

masters echoed the mountains and waters that surrounded my school. They and the

Saturday art lessons in the studio of Prof. Sun To-Ze helped plant the seed for

my journey in art across the oceans.