SHORT STORY

NARAYAN DHAKAL

Renegade

There were three people in the southeast corner—two men not yet middle-aged and a woman, younger still. As soon as I passed through the door, my eye fixed first on the woman among them. She was toying with mounds of soft chow mein. When my attention turned to the men, I saw that they were blissful with vodka's intoxicating heat.

I sat down on a chair near the door. The rest of the

restaurant was entirely empty—like a despondent person's mind. At the counter,

the proprietress was nodding off. That motion of hers looked a bit

uncomfortable. Anyway, she had no interest in her duty toward the three in the

corner. Business activity had not made any impact on the two waiters standing

by the opening to the kitchen either. In other words, the situation created a

heavy burden in my mind alone. I was stooping under its weight. My mind was despondent.

Since morning, my heart had been thudding. Why? Even I

didn't know. It's like this with me sometimes. I'll be that despondent—just

like a sentimental poet.

The hot weather had just ended in the city, and about a

month had passed since the monsoon. Already, after four in the morning, fog had

begun to waft through the alleys. There was a feeling of sharply increased cold

in the interior of the restaurant. Compared to other places in the city,

though, this alley remains somewhat cool even in times of unbearable heat. A

cold dampness and a special kind of smell always envelop it. I've known its

atmosphere for many years—I have a deep friendship with it. Whenever I have to

leave the city, the intense recollection of this smell comes to me and

seriously affects my nervous system. Like a character bereft of lover or wife,

I become restless.

Thus, I can never sleep here in the afternoon.

But why was the proprietress nodding and waking, nodding and

waking so uncomfortably? For a long moment, I was bothered by this useless

question.

"Is there milk, brother?" I asked the waiter who

stood mechanically before me.

"Milk?"

"Yes, milk," I said firmly.

"This is a bar, sir. There's no milk in a bar."

"No milk? Then what is there? Is there tea?"

"There's vodka, Khukuri rum, Challenger,

Bagpiper."

"And what else?"

"There's also tongba."

"No dairy milk?"

"That there is not."

The other waiter, who stood near the hole in the wall that

opened to the kitchen, overheard this dialogue and was smiling. He'd been

around here for a while, so he knew me. But this boy was new.

"Are you new here?"

"Yes, sir."

"When did you come?"

"Just a month ago, sir."

"Ah... in that case, just bring a glass of water."

"Sir, won't you drink tongba?" said the waiter

again after putting the water on the table.

"I can't drink it, this city tongba," I answered

in the tones of the grousing old woman in the spice company ad.

This answer didn't have any effect on the waiter, for he was

ignorant of the ad. But the waiter near the kitchen began to grin.

"Hey, cut the laugh... shameless ass," I

threatened him—in a joking tone but as if serious.

After that, he sealed his lips over the rest of his

laughter. The new waiter got out of there and, showing his discomfort, stood

close to the old waiter. He was not understanding the city. The city is not

easily understood. It takes a long time. Moreover, for the poor, this

understanding amounts to a Mahabharata.

The three people in the corner were really getting into

drunken displays of emotion now. Vodka intoxication was steadily awakening a

sharp awareness of their manhood within the male pair, and its refraction could

clearly be seen reflected in the woman. In this restaurant, such happenings are

considered commonplace. The regulars here are mostly lovers who can mortgage

their own honor or urban prostitutes who defy honor. Yet the restaurant owner

is not as ill-reputed as the restaurant itself. In Sherpa society, setting up a

hotel is not considered an immoral occupation. Furthermore, the owner is a

person who, after working for some time in a social-democratic party, has just

joined a Communist Party.

When the telephone's shrill bell suddenly sounded at the

counter, the proprietress, who had long been nodding and waking, was scared out

of her wits. She rose in a panic from the chair and rushed toward the

telephone.

"Hallo!"

No sound came from the other end. Irritated, she slammed the

phone down.

"Why are you dozing off, huh? Did the old man keep you

up all night or what?" I said to the proprietress in a teasing way.

But she just smiled and rushed off toward the bathroom.

Amid all this, a middle-aged hill-style man carrying a cloth

bag passed through the doorway. His attire of kamij-suruwal and the

salt-and-pepper beard growing in anarchic fashion on his face directly gave

away his identity—he was a resident of some eastern hill village. His age might

even be much less than I thought. The dreadful poverty of the village and the

murderous privation that the body cannot endure make anyone old before their

time. So then, how could he be the one exception to this?

He stood a moment near the counter, confused. The

proprietress had still not returned from the bathroom. After glancing around

for a moment, he began to look toward the rear of the restaurant. It was a very

spacious place, this restaurant. It's possible that there's not even a library

in the city that could hold so many people.

He first looked toward the corner. Then, acting a little ill

at ease, he came and stood near me.

"Have a seat, why stand?"

"Where might Comrade Lakpa be?"

"What Lakpa?"

"Isn't this his hotel?"

"Ah... Lakpa Sherpa. Is your home around Taplejung too,

or what?"

"Yes. It won't do for me not to find him."

Exhibiting great innocence, he began to look into my face.

"I haven't seen Lakpa today either. Ask the

proprietress when she comes. Sit down a moment though. Rest yourself."

After my urging, he

was compelled to sit.

"So then, what business have you come to Kathmandu

for?" I opened up the bundle of questions.

"I came to meet Comrade Navin."

"Who's Comrade Navin?"

"Now, what to say! That's the name I know. During the

Panchayat regime, he worked secretly in our district. He stayed many times in

my house too. A very good person he was. I too did much service. The police

were searching for him. I heard there was an order to shoot on sight. How many

times he had to shit and piss inside the room! Without any disgust, I would

empty his chamber pot. But now, where is he...?"

"That was many years ago, though. It's already been

nearly a decade since the Panchayat fell. Now, who can arrange for you to meet

the one you call 'Comrade Navin'? Who might even remember that name from the

underground days?"

He was greatly encouraged by my response. Rushing with

happiness, he said, "What, do you work in the Communist Party too?"

Seeing him preparing to rise from the chair, I said,

"Don't rush, don't rush."

"What level of the Party do you work in?"

"I'm not a Party worker. Until some days ago, I was a

correspondent for a private-sector daily newspaper. Now, having been tossed

out, I'm unemployed."

After that, he looked depressed.

"But still, I'm very interested in politics. Because of

my profession too, I was compelled to know a lot about it," I said,

intending to intervene in his gloom.

"Then you don't know Comrade Navin, isn't that

so?"

"Why are you searching for Comrade Navin? Is it to get

jobs for your children or what?" I asked, thinking he'd already passed the

age for holding a position himself.

"They're not children capable of holding a position,

mine aren't, sir."

After answering, he looked extremely sentimental. In a

moment, like a saturated clay water pot, his eyes glistened with wetness.

Why was he so emotional? My heart refused to enter

compassionately into the tangled events. I was in no way ready to make him

suffer more by picking at his wounds. And then, too, why carry another's pain

at a time when my own heart was as irregular as the pendulum of an old clock?

"If you want to meet Comrade Navin, go to the Balkhu

office. Maybe in the Party's old records—who this Comrade Navin is, I

mean," I politely advised him.

"I went there. Yesterday morning, before it had even

struck seven, I arrived. The office wasn't open. After waiting around for three

hours, it finally opened. But the soldiers and office workers sitting there

said, 'There's no one called Comrade Navin here, and not in our old records

either.'"

***

Saying, "Maybe in some other party," they sent me

away. "I only knew him."

"So, haven't you asked the comrades of your district,

'Who is he, Comrade Navin?'"

"No one gave a good answer. Now, Comrade Lakpa may know

about this matter; otherwise, it can't be discovered from others. Only here,

there's one last hope."

"Isn't Lakpa a newcomer, though? What might a new

member, of all people, know about old matters? Who might even remember that old

history now?" I expressed my doubt again.

Finally, after such a long time, the proprietress returned

to the counter. The middle-aged villager rose and moved toward her.

"Where's Comrade Lakpa, sister?"

"He left for da district, first t'ing in da

mornin'," she answered in the Sherpa style of speaking Nepali.

"Headed for the district? Now disaster has really

struck!" Like a traveler whose dream had been lost, he let out a sigh.

"Yesterday was da Contact Front 'lekshun, he sed. He

won in da President, I hear. Feasted all night. Sang songs. And t'en, firs'

t'ing in da mornin', off to da hills."

The villager again became baffled and began distractedly

looking outside. After puzzling for a moment over whether or not to leave, he

came over to me once again and, sitting down, said:

"Why does the Mahakali Treaty have to be done? Who

knows? I wanted to hear it once from the mouth of Comrade Navin. But now, who

can say where he is?"

I couldn't understand at all whether this villager was

wounded by or glorified the Mahakali Treaty. I even asked a couple of questions

to figure it out. But he just kept on reciting, "Comrade Navin, Comrade

Navin..."

"So long as I don't hear Comrade Navin's reasoning, how

can I set out my own opinion?" Suddenly riled, he hurled this answer at me

like a projectile.

"You just carry on and on, saying 'Comrade Navin,

Comrade Navin...' At some point, that secret name of an underground party

leader will have been lost amid the ruins of the underground times. Where

within that party are you going to come across it now? And how long are you

going to race around like this, as if insane, trying to get a certificate

saying whether the Mahakali Treaty was right or not?"

"Forgive me. I'm not in agreement with your views.

Comrade Navin is the name of a god who resides in my soul. We were together

during much hardship, many crises, and many great difficulties. He is a witness

to my poverty and terrible hunger. How could Comrade Navin, a strong advocate

of democracy, nationalism, and the people's livelihood, so easily forget

Taplejung's poor peasant, Haribhakta Karki, in that way? If you'd been in that

situation, you'd think this way too. Understand?"

Finally, I found out his name—Haribhakta Karki. He was very

agitated. His eyes, which had been brimming a while ago, were glistening again.

Then he became very silent and, resting his elbows on the restaurant table,

bowed his head and began to ponder.

"Does Comrade Navin have no existence at all then, in

this country?"

The noise from the southeast corner began to increase again.

Of the two men, the short, fat one looked very agitated. He was performing

various shenanigans to show off that he was a big-time businessman of the city.

But from his staged display, you could tell he was a land agent earning money

hand over fist—like he'd just won the lottery.

The main activities he had just embarked on were to jump up,

go over to the counter, make a phone call, and then, returning to his place,

carry out a concerted campaign to win over the woman who was there. This time

too, he rose and made his way to the counter. And just like before, he started

punching the English numbers stuck to the telephone.

"Hello!"

What the answer was, I didn't know.

"Listen up. Put a lock on those three phones. Don't let

anyone make a call. All kinds of useless sons of bitches come to make calls.

Unemployed idlers make me furious. Son of a bitch penny-pinchers... Understood?

Today I may not make it there. The plan is to go to Dhulikhel or Nagarkot

around evening. If yesterday's client comes, tell him to come at 10 o'clock

tomorrow. Oh—and those phones—don't let anyone touch them."

After saying that much, he returned to his place.

"Sons of bitches, can't make two cents of profit."

"Instead, coming around to make phone calls, they just

make a nuisance of themselves. See how it is, love?" he added after

sitting down cross-legged and massaging the woman's shoulders.

The other man who was there looked a little more polite than

the short, fat one. His entire activity consisted of nodding his head. As I

watched, they finished off half a bottle of vodka and moved on to another

quarter.

"Sons of bitches carry on like it was their own

father's wealth. In the final analysis, I'm not their father though, am I now?

Or how is it?"

The other man and the woman didn't express any agreement

with his outburst. Perhaps that burned him up, for at that moment, he shouted:

"What, you two don't believe it either? Eh Gope, you

don't believe it either, or what? You ass, you've been to my office a thousand

times!"

The woman definitely didn't like Short-and-Fat’s vulgar

manner. She signaled with her eyes to the one called 'Gope' to get up from

there. In the same way, he signaled to the waiter to bring the bill. There was

about a peg left in each of the two men's glasses.

Short-and-Fat was in favor of sitting for a long time yet,

so he said, "What's the rush all of a sudden? Our car won't come before

five o'clock, isn't that right? Why sit around making unnecessary small talk?

In the meantime, come over to my office one time. Going here and there, doing

this and that, it'll be five before we know it."

"What's that I hear—I made unnecessary small talk? You

son of a bitch, Gope, what unnecessary small talk have I made? Did I talk about

the Mahakali Treaty?"

"Who said you talked about the Mahakali Treaty?"

said the polite man, trying to smooth things over.

But Short-and-Fat paid no attention. Playing the classic

drunkard, he said, "Let it be damned—Mahakali, Sahakali."

Haribhakta, who had been sent into depression by our

previous conversation and had been sitting with his face down on the table,

started up. He began peering toward the corner.

In the meantime, after dropping money on the bill the waiter

had presented on a plate, those three walked out of there.

"Anyone at all will be like that after drinking,"

Haribhakta politely commented.

"It's not everyone who's like that after drinking—it's

renegades who'll be like that. Understand?" A bit agitated, I expressed my

own reaction.

"Renegades? Who are you calling a renegade? What were

those renegades?"

"Yes, among the crowd of renegades, those too were one

kind of renegade. Renegades of '96."

I didn't know if Haribhakta understood this talk or not. He

was stymied by his own inner turmoil.

"Well then, I'll be going too. If we meet again one

day..."

Waving his hand, he walked toward the counter, took leave of

the proprietress, and exited.

After that, I was alone in the restaurant. My solitude made

the environment all the more uncomfortable. The waiter, who had just arrived

from the hills, seemed uneasy about me not ordering anything. He came over

again and started to whine:

"Won't you drink tongba, sir?"

"No tongba. If you can bring it from outside, I'll have

a glass of milk."

Just as before, I gave a withering reply and, taking a stale

newspaper from my bag, began to read.

Now the waiter was really confused. With a befuddled

expression, he headed for the counter where the proprietress sat. But just like

before, the proprietress was once again participating in the national program

of nodding off.

Translated from the Nepali by Mary Deschene & Khagendra Sangraula

Nepalese novelist and

political activist Narayan Dhakal has published various books, including

Pretkalpa, Peet Sambad, Shokmagna Yatri, and Brishav Vadh, among

others. He lives in Kathmandu.

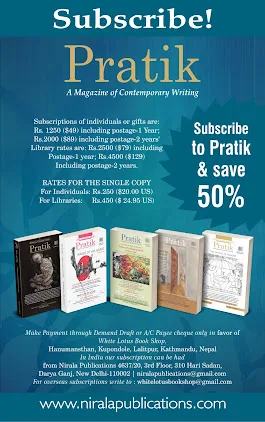

Also Available on Amazon, Flipkart & Daraz

Amazon USA: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0DWSPT5WP

Amazon India: https://www.amazon.in/dp/B0DWSPT5WP

Distributed in the United States by Itasca Book

Distribution: https://itascabooks.com/ Distributed

in South Asia by Nirala Publications, India: https://niralapublications.com/product-category/pratik-series/ In

Nepal by White Lotus Book Shop, Kathmandu: https://whitelotusbookshop.com/product-category/pratik-series/